Fortifications of Vauban

By Rachel Heller

What are the Fortifications of Vauban?

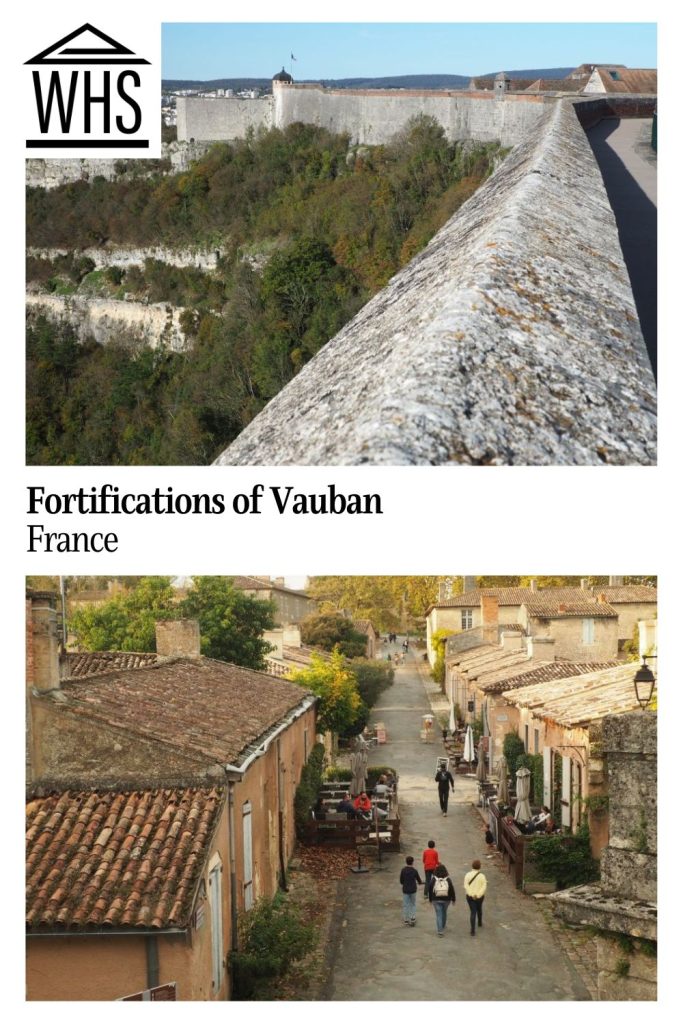

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707) was an architect who worked for King Louis XIV as a military engineer. In that capacity, he designed fortresses all around the borders of France. He also designed towns to go with some of them, as well as various bastions and other military structures. His fortresses are distinctive in their designs that use and accentuate the location’s geographical features in the interest of a strong defense. Many of them also have a distinctive star shape in their bastions, walls, ditches and/or moats: the pointed corners allow complete views of any possible intruders.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. Making a purchase through an affiliate link will mean a small commission for this website. This will not affect your price. Privacy policy.

This serial UNESCO site includes 12 separate sites, which, in themselves, often contain several distinct structures:

- Arras: A citadel.

- Besançon: A citadel, a city wall and Fort Griffon.

- Blaye: A citadel, Fort Paté and Fort Médoc.

- Briançon: A city wall, the forts of Salettes, Trois-Tête, Randoouillet and Dauphin, Y communications and the Asfed bridge.

- Camaret-sur-Mer: Dorée Tower.

- Longwy: A fortress.

- Mont-Dauphin: A fortress.

- Mont-Louis: A wall and a citadel.

- Neuf-Brisach: A fortress.

- Saint-Martin-de-Ré: A citadel and a city wall.

- Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue: The observation towers of Tatihou and la Hougue.

- Villefranche-de-Conflent: A wall, a fortress and la Cova Bastera cave.

Why are the Fortifications of Vauban a UNESCO World Heritage site?

Vauban is a major figure in the history of fortifications and influenced military architecture for the next two centuries or more. As UNESCO states it, “The imitation of his standard-models of military buildings in Europe and on the American continent, the dissemination in Russian and Turkish of his theoretical thinking along with the use of the forms of his fortification as a model for fortresses in the Far East, bear witness to the universality of his work.”

There were more forts that he built both inside and outside of France – for example, he contributed to Luxembourg‘s fortifications – but these 12 were chosen because they were considered to best represent his work.

What can you expect on a visit to the Fortifications of Vauban?

Judging by the three that I visited – Besançon, Blaye and Longwy – each one offers a different experience. Most are intact and well-maintained, ready for visitors. Some are whole towns designed by Vauban for the soldiers, families and businesses supporting the troops in that fort. And some are relatively small, consisting of one or two structures.

Here’s a summary of each, and at the bottom of this article you can find a list of their websites for more information:

Arras: La citadella

The Citadel of Arras is now a park in the middle of the city of Arras, near the border with Belgium, with park and nature areas both inside and outside the walls. The large entryway (Porte Royale) and the buildings inside the fortress still stand because it never experienced an attack, though it did take some damage during World War I. Three of the original five bastions are also still there.

Today the former barracks and armories are residential housing and some businesses as well. You can learn about the fort’s history in the Salle de Familles and you can walk around the ramparts of the star-shaped citadel, or take a longer route around the outside of the fort.

Besançon: La citadelle, l’enceinte urbaine et le fort Griffon

We visited this fortress and it was immediately apparent why Vauban’s designs were so special. On top of a rocky outcropping with rivers on three sides, it would be very effective to defend. The walls are designed to deflect cannonballs. Walking around the citadel walls makes it particularly clear how high up the fortress is and how far the defenders could see from that height.

Today, the fortress is home to three museums:

- The Museum of Resistance and Deportation is centered around how, during World War II, ordinary people resisted the Nazis. We visited this museum and found this particular story very interesting, though the exhibits are pretty static.

- The Museum of Besançon covers natural history, both in museum form and in the form of a zoo. The zoo animals, many of them housed inside the former dry moats, are the subjects of conservations projects.

- The Comtois Museum looks at the history and culture of the Franche-Comté region.

We didn’t visit it, but Fort Griffon is visible in the distance on a hill opposite the citadel – as are other forts, built later than Vauban’s. Fort Griffon dates to the 16th century but Vauban redesigned it. Today it is home to a teacher-training college but can also be visited.

Blaye: La citadelle et le fort Paté et Médoc

This is a set of three fortresses: Fort Paté, Fort Médoc and the Citadel of Blaye. The idea was that, together, they could stop invasion of the important city of Bordeaux via the river Gironde. At the time, Bordeaux was an extremely important trading city.

Fort Paté is a round, stubby tower on an island in the middle of the Gironde river off the town of Blaye. It was a good place to keep an eye on ships approaching from the estuary to the north. It is private property, closed to the public.

Fort Médoc sits opposite it on the bank of the river. It is open to the public, but there doesn’t seem to be much to see there.

The citadel itself is in the town of Blaye, and is essentially a village on the edge the city. Entering through the grand entryway – after crossing an enormous moat via an arched bridge – places the visitor in a charming street of stone houses and quirky little shops. These would have originally served as barracks and other work buildings to support the soldiers housed there. We enjoyed walking its grid of streets and reading the informational signs posted here and there to explain what we were seeing.

This fortress is not on very high land, though it is raised above the river, allowing a clear view of the river and the island where Fort Paté stands.

Briançon: L’enceinte urbaine, les forts des Salettes, des Trois-Têtes, du Randouillet et Dauphin, la communication Y et le pont d’Asfeld

Completed to Vauban’s plans but after his death, the multiple fortresses defend the town of Briançon, in the mountains near the Italian border. There are four forts and several other structures scattered around the city:

Fort Trois-Têtes is the most important of Briançon’s fortresses. It contains barracks, an arsenal, various other storage spaces for armaments, as well as whatever was needed to supply the soldiers, like a bakery, stables, and so on. Guided tours are available.

Fort Salettes sits on a craggy point above the city. Quite a small place as fortresses go, it has a square tower, a dry moat and a gallery overlooking the moat. It is home to an association that maintains the fort.

Fort Randouillet was not designed by Vauban, but was added to his multi-fortress design later in his characteristic style. Its function was to prevent attack from above the city and to protect Trois-Têtes fort. There’s a guardhouse and a barracks, watchtowers and the usual support buildings.

Fort Dauphin, like Fort Randouillet, is placed in such a way as to help protect Trois-Têtes from attack from the road above. It’s not very big, containing a barracks and some bastions and not much else.

Communication Y is a 200-meter-long (656 feet) fortification that cuts right across a valley, forming a barrier as well as a way to move from one side of the valley to the other (between Fort Trois-Têtes and Fort Randouillet) while protected. Above and below it are ditches and bastions that would make it hard to attack either from uphill or from below. Guided tours are available.

Asfeld Bridge spans a deep gorge and the Durance river with a single elegant arch. It connects the hill on which the Fort du Chateau stands and the two hills topped by Fort Trois-Têtes and Fort Dauphin.

Speaking of Fort du Chateau, that is almost all a later construction. Only its powder magazine was designed by Vauban.

Vauban also designed the town of Briançon itself – at least the old part of it. His fortifications around the town are part of the UNESCO designation too.

Camaret-sur-Mer: La tour Dorée

Unlike in Briançon, this part of the UNESCO site is essentially a single building. Dorée Tower, also called Vauban Tower, in Camaret-sur-Mer is a defensive tower in a hexagonal shape, covered in crushed brick. Its purpose was to protect a battery next door which in turn defended the harbor along with other batteries along the coast. Only a handful of soldiers manned the tower.

Accommodations in Camaret-sur-Mer.

Longwy: La place forte

This was one that my husband and I visited, and it presented a rather forlorn appearance. Some of the bastions and earthen embankments are still there, as well as one of the large entryways – the Porte de France – and barracks, bakery, town hall, and a church. Much of the rest was damaged in World War I or World War II and/or collapsed later.

It all seems to be open and deserted, though it does seem to be maintained to some extent. The pavement on the walkways is in good shape and someone had mown the grass when we visited in October. We saw only a few people walking dogs, and it looked like some of the storage spaces – missing doors – were being used as shelters for homeless people.

Mont-Dauphin: La place forte

Like at Besançon, Mont-Dauphin is a complete fortified town designed by Vauban. It sits on a plateau in the Hautes-Alpes at a point where two valleys join. Together with Briançon, it was meant to defend France from attack from Italy. The town itself is open all the time, but the only way to see the fortifications and the military buildings is via guided tour.

Accommodations in Mont-Dauphin.

Mont-Louis: L’enceinte et la citadelle

Mont-Louis is another town and fortification designed from scratch by Vauban, in this case to defend the country against Spain. The fortress itself comprises barracks for 2500 soldiers around an open courtyard, powder magazines, and other service structures, all protected by a series of ramparts, ditches and so on. Its large entranceway – Porte Saint-Louis – leads to the civilian town below.

Because the citadel is still used by the French military, it can only be visited on a guided tour. The town is always open.

Neuf-Brisach: La place forte

This fortified town on the Rhine river guards the border with what was, at the time, the Holy Roman Empire. It was built from scratch to Vauban’s design in an octagonal shape with a street plan of square blocks and a fortified perimeter. Blocks of housing just inside the wall for the poorer inhabitants helped protect the homes of wealthier citizens further toward the center from cannonfire. The exact center of the town is a four-block square with a church.

Beyond the city walls are the usual bastions in a star shape. Interestingly, though, this town isn’t high on a hill like so many of his other fortresses. The idea was that if troops crossed the river here, they’d be exposed and quite close so the troops in the fortress could fire on them.

Inside the ramparts is a street-art museum called MAUSA Vauban. There’s also a small museum about Vauban and the construction of Neuf-Brisach inside one of the entranceways: the Porte de Belfort.

Accommodations in Neuf-Brisach.

Saint-Martin-de-Ré: La citadelle el l’enceinte

The purpose of Saint-Martin-de-Ré’s citadel was to defend La Rochelle and Rochefort from the English. The citadel is square and has only a single entrance facing a small harbor. It contains the usual range of barracks (housing 1,200 soldiers) and supporting buildings. Vauban also designed the defensive wall that extends from the citadel and around the old part of the city.

Accommodations in Saint-Martin-de-Ré.

Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue: Les tours-observatoires de Tatihou et de la Hougue

This site is made up of two observation towers on the Normandy coast: Tatihou and La Hougue. Together with the Fort de la Hougue (not a Vauban fort), they protected the bay at Saint-Vaast from attack by the English.

Tatihou is a small island off the coast opposite the town of Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue. Its Vauban-designed tower stands at one corner of the island, 21 meters (69 feet) wide and almost as wide, with earthen bastions and moat in a four-pointed star shape.

Nowadays, the island is a bird sanctuary. Access is only by amphibious boat from Saint Vaast. Besides birdwatching, you can visit a maritime museum and gardens on the island. It can only be visited from April to November and the number of visitors per day is limited, so you need to book your tickets ahead.

Accommodations in Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue.

La Hougue is very similar to Tatihou and is located just under three kilometers away in Saint-Vaast. It is the exact same height but not as wide around, yet it looks bigger because it stands on a hill 20 meters high. Owned by the French military, it is open to the public during the summer months.

Villefranche-de-Conflent: L’enceinte, le fort et la Cova Bastera

At Villefranche-de-Conflent, in the Pyrenees near the border with Spain, the Vauban designation includes three parts: the ramparts around the city, Fort Liberia, and a cave called Cova Bastera.

The ramparts around the town of Villefranche are unusual in that they have two levels, allowing defenders (and today’s visitors) to patrol two paths. The upper one is roofed. They rest on top of the original medieval walls, and some of the original medieval towers are integrated into Vauban’s design.

Fort Liberia overlooks the town of Villefranche. Not shaped in the usual square or star pattern, the fort occupies a rather narrow outcropping, so its structure is more linear. The buildings inside the fort are mostly complete, with a later addition of a long underground stairway down to the town. While it is private property today, it is open to the public.

Accommodations in Villefranche-de-Conflent.

La Cova Bastera is a fortified cave. It was a natural cave originally, but Vauban designed its fortification, which was carried out after his death. A staircase connects it to the town. Today, it houses a theme park of sorts called Dinopédia.

Vauban did not design the town of Villefranche itself. It dates to the Middle Ages, and is still largely intact inside its walls, which makes it very charming.

Are the Fortifications of Vauban worth visiting?

I would say that yes, some of them are, at least if you’re in the general vicinity. Besançon, Blaye, Briançon, Mont-Dauphin, Neuf-Brisach, and Villefranche-de-Conflent all sound like they have enough to see to be worth a day at least, both because they have interesting fortresses and because they have whole towns inside them – except for Besançon, which, instead, has several worthwhile museums. Of these, I’ve seen Besançon and Blaye, and while they’re quite different from each other, they both had plenty to keep us interested for hours.

What sorts of travelers would like the Fortifications of Vauban?

Anyone interested in military history and architecture should see at least one of these. But they’re also just remarkable structures in remarkable places. Most of these perch on hills or mountains, which means they offer wonderful views, but it also means you’ll have to do some walking. I’d imagine that’s particularly true for the ones in the Alps or the Pyrenees.

It seems to me that any of these bigger fortresses would appeal to children. They would enjoy exploring ramparts and pretending they’re soldiers. In addition, many of the fortresses have activities and/or attractions meant to appeal to kids.

Tips for visiting the Fortifications of Vauban

Some of the fortresses are quite close to each other so they could easily be combined.

- Villefranche-de-Conflent and Mont-Louis are about a 40-minute drive apart. There’s also a special “Yellow Train” that connects the two, passing through a mountainous landscape and a nature reserve on the way. Carcassonne, another UNESCO site, is not far away.

- Briançon and Mont-Dauphin are also about 40 minutes apart.

- The two towers in Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue are very close together: one is on the mainland, while the other requires a short ride in an amphibious vehicle.

While the towns are open to the public, make sure to check the opening hours and days for each fortification you want to visit. Many of them close altogether in winter. Some are only open for guided tours, so you’d need to reserve a place. See the websites listed below.

Wear solid, supportive shoes. The walkways are generally well-paved, but can be uneven. Hold on to railings on the stairways, which can be very long and sometimes a bit worn in places. Keep a close eye on your children since most of the forts are very high up.

Some of these fortresses might be wheelchair accessible, but only partially. The ramparts involve stairs. Again, check the websites to read each location’s accessibility information.

Depending which part of France you’re in, there’s likely to be other UNESCO sites nearby; France has 53, and many of them, like this one, are so-called “serial properties.” See our France page. For example, the fortress in Arras is near many of the Belfries of France and Belgium serial property, including the belfry in Arras itself.

Where are the fortifications of Vauban?

Here are the nearest cities of any size to each of these locations. Please be aware that all of the driving times listed below are based on there being no traffic or road works! Nevertheless, driving will be far easier than public transportation to any of these. Take a look at car rental prices here.

- Arras: About halfway between Lille and Amiens. It’s about 1 hour 15 minutes’ drive from Amiens, and a bit less by train. Lille is about an hour away by train and 45 minutes by car.

- Besançon: The nearest city to Besançon is Dijon, about 1 hour 15 minutes by either car or train.

- Briançon: Briançon is about halfway between Grenoble and the Italian city of Turin. The bus trip from Grenoble would take 4-5 hours, while driving would take about 2 hours 20 minutes. From Turin the drive would be 1 hour 45 minutes. There is no train connection from Turin and traveling by bus would be extremely complicated and time-consuming.

- Camaret-sur-Mer: Located on a peninsula, Camaret-sur-Mer is about an hour’s drive from Brest in Brittany or about 1 hour 10 minutes from Quimper. I don’t think you can get there by train.

- Longwy: The nearest city to Longwy is Luxembourg, about 45 minutes away. The quickest bus route would take about 1 hour 10 minutes. From the French city of Reims, the drive is about 2 hours and 10 minutes – more if you avoid the toll highway. Taking buses would take about 5 hours.

- Mont-Dauphin: The nearest cities to Mont-Dauphin are Grenoble in France and Turin in Italy. From Grenoble, driving will take 2 hours 45 minutes. Taking buses will take many hours more. It’ll take 2 hours 30 minutes to drive from Turin. There is no train connection from Turin and traveling by bus would be extremely complicated and time-consuming.

- Mont-Louis: Perpignan is the nearest city to Mont-Louis. By car it’ll take 1 hour 15 minutes, while by bus it’ll take 3 hours and involve several transfers.

- Neuf-Brisach: Neuf-Brisach is 30 minutes’ drive from Colmar and 40 minutes by bus. Getting there by bus will take anywhere from 1 hour 40 minutes to almost 4 hours, depending on which routes and buses you choose. By car from Mulhouse will take about 45 minutes.

- Saint-Martin-de-Ré: La Rochelle is very near to Saint-Martin-de-Ré: 30 minutes by car. From Bordeaux it’s 2 hours 15 minutes’ drive, and from Nantes it’s 2 hours. I can’t seem to find info about taking public transportation; Saint-Martin-de-Ré is connected to the mainland by a single bridge.

- Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue: The nearest city is Cherbourg, where many of the ferries from England and Ireland come and go. By public transportation it’ll take about 1 hour and 15 minutes from Cherbourg, while by car it’ll take only 30-40 minutes. Caen is a bigger city to the southeast of Saint-Vaast , about 1 hour and 20 minutes away. Getting to Saint-Vaast from Caen via public transportation would take pretty much a whole day.

- Villefranche-de-Conflent: About halfway between Andorra and Perpignan. About 45 minutes’ drive and 1 hour 30 minutes by train from Perpignan.

For more information about any of the 12 sites within this UNESCO designation, their opening hours and admission fees, see the corresponding websites below. Many of these are only available in French. I use a browser extension of Google Translate, which instantly translates any page for me. There’s also a website about this UNESCO site as a whole, with information on all of the 12 locations: Fortifications de Vauban Patrimoine Mondial de l’UNESCO.

- Arras

- Besançon Citadel and Fort Griffon

- Briançon: Fort Trois-Têtes, Fort Salettes, Fort Rondouillet, Fort Dauphin, Communication Y, Fort du Chateau

- Camaret-sur-Mer

- Longwy

- Mont-Dauphin

- Mont-Louis

- Neuf-Brisach

- Saint-Martin-de-Ré

- Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue: Tatihou tower, La Hougue tower

- Villefranche-de-Conflent, Fort Liberia, Cova Bastera / Dinopedia.

Have you been to any of these fortifications? If so, do you have any additional information or advice about this UNESCO World Heritage site? Please add your comments below!