Schokland and Surroundings

By Rachel Heller

What is Schokland and Surroundings?

Schokland is a small area with a long history of battling with the sea. The landscape was formed by ice ages that left sand and boulder clay. Rising sea levels added sediments and created peat lands.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. Making a purchase through an affiliate link will mean a small commission for this website. This will not affect your price. Privacy policy.

It was wetlands and rivers when the first prehistoric people passed through as hunter-gatherers. The first settlements here involved building small mounds called terpen (singular: terp) to raise houses and livestock above flood levels. Schokland was a peninsula by the Middle Ages, home to several terp villages, but it shrank with every storm until 1450, when a storm made it an island.

The Zuiderzee (which means “southern sea” and is now the Ijsselmeer) encroached on this area gradually. The residents of Schokland turned to fishing instead of farming.

The same was happening to other terps nearby, and they were abandoned one by one when new, larger terps were built in the region. Schokland’s communities – Protestants in the north of the island and Catholics in the south – held on, though, and did everything they could to strengthen their little island. They lined the banks with wooden stakes and tried dikes made of rock as well. They also raised their four island terps higher. Since the shipping routes passed by here, the lighthouse on the south point of the island was important, so the governments of Holland and Friesland gave financial support. Later, the financial responsibility shifted to Amsterdam.

The few hundred inhabitants of the island were very poor by the 18th and 19th centuries. Fishing wasn’t very lucrative, and paid work was mostly seasonal: working on the dikes around the Zuiderzee.

Their efforts were to no avail in the end. Storms kept causing damage, eating away at the island. Finally, in 1859, the remaining population – only about 650 people – moved away, taking their homes apart so they could use the building materials to start over elsewhere. The island became a breakwater with only a couple of remaining buildings. A harbormaster and a lighthouse keeper remained, and seasonal workers lodged in one of the churches.

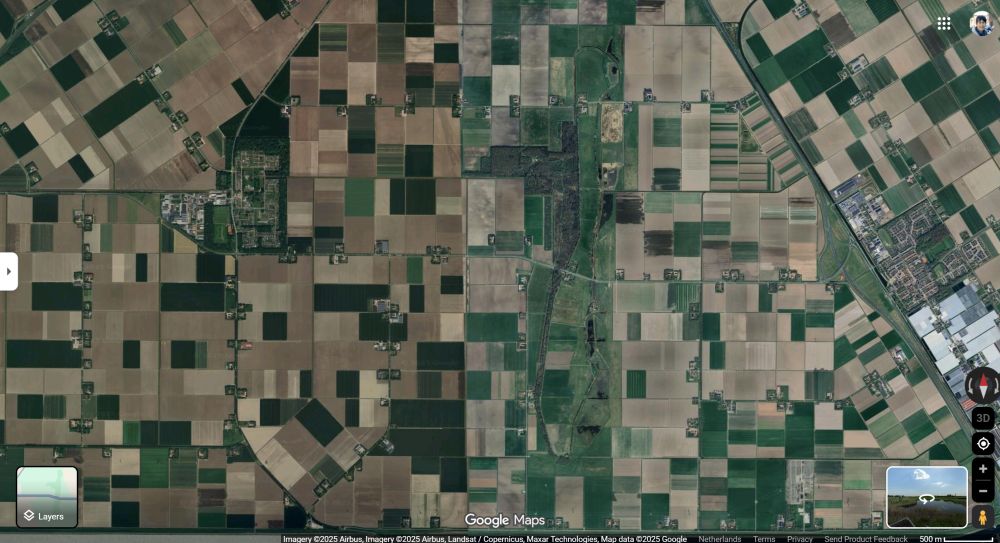

In the 20th century, a huge project began with the aim of creating land by building a long dike – the Afsluitdijk – across the mouth of the Zuiderzee and draining parts of the sea. The second part of this project happened in the 1940s and became what is now known as the Noordoostpolder. A polder is land that was once the seabed but has been drained and surrounded by dikes to keep the sea out. In this case, the polder surrounded Schokland. Today, the UNESCO-designated area is farmland, and what used to be the island of Schokland rises only very slightly above the flat landscape, nowhere near the sea.

Why is Schokland a UNESCO World Heritage site?

As the Netherlands’ first UNESCO site, Schokland “symbolizes the heroic, age-old struggle of the people of the Netherlands against the encroachment of the waters.” The UNESCO designation includes the former island of Schokland and the four village terps on it, another site where researchers found traces from the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age, and other archeological sites in the surrounding area.

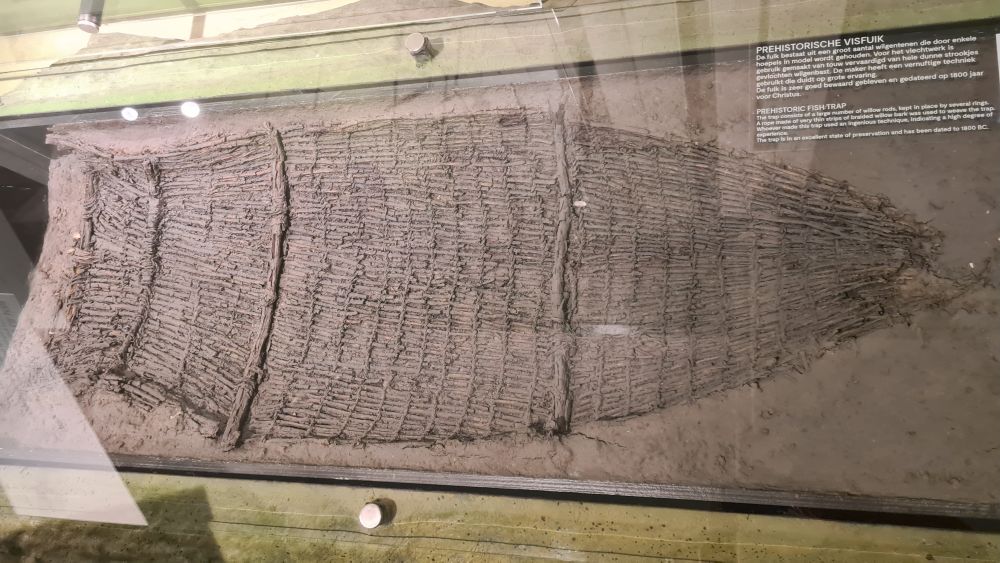

Many archeological remnants only came to light when the area was drained. As UNESCO puts it, Schokland is important because the area preserves “the last surviving evidence of a prehistoric and early historic society that had adapted to the precarious life of wetland settlements under the constant threat of temporary or permanent incursions by the sea.”

It also stands as a representative of the importance of the entire Zuiderzee project, “one of the greatest and most visionary human achievements of the twentieth century.” The Zuiderzee, once part of the North Sea, is now a smaller freshwater lake: the Ijsselmeer. The Ijsselmeer is no longer part of the sea, though there are locks where ships can pass through to the Wadden Sea and the North Sea. The entire province of Flevoland was created in this polder-making project, and the Noordoostpolder is part of that province.

What can you expect on a visit to Schokland?

If you didn’t know it was there, you wouldn’t even know there was anything special about the former island of Schokland. It looks like farmland and some woods. Yet the contours of Schokland are very clear when you look at aerial photos.

Today the slightly raised part of Schokland where the village terp of Middlebuurt once was, houses a museum about the history of the area. It displays many artifacts uncovered when the surrounding sea was drained. I didn’t expect much when I stopped here, but it turned out to be quite an interesting story covering many centuries. The area’s history starts with prehistoric animals like straight-tusked elephants and cave bears. The museum traces the history through the humans who settled here, how they lived and their battle with the sea, all illustrated through the items they left behind.

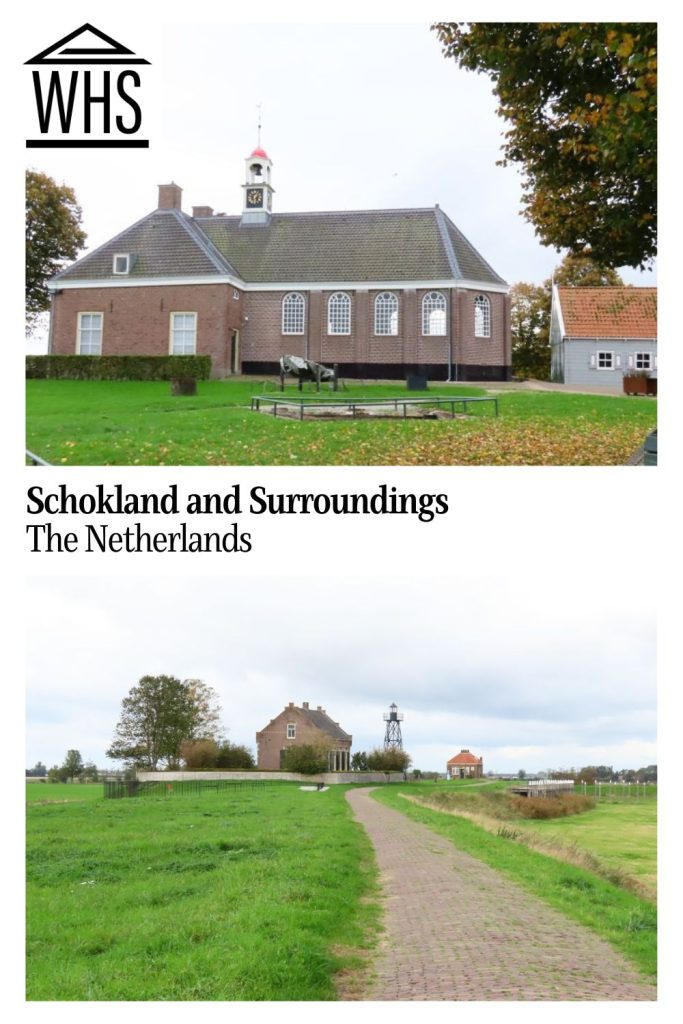

Part of the museum is a church, now used for temporary exhibits. It’s not the original church in this location; the old one was badly damaged in a storm in 1825. This one replaced it in 1834.

The homes of the island’s last inhabitants were all torn down when they left, but a few sets of foundations remain. A trail around the museum grounds passes remnants of their lives and of objects uncovered as the polder drained: some anchors, some of the old wooden piles and the stone dike, the village well and other finds. Several modern artworks memorialize the residents who tried so hard to defend themselves from the sea.

The former island has other sights to see. An 11-kilometer biking and walking trail (7 miles) circles it, passing the remains of the island’s terp villages as well as the Gesteentetuin.

The Gesteentetuin focuses on the geology of Schokland and the rocks that were left here in the last two ice ages. It has its own visitors center with an exhibition and a children’s play space in the attic.

The harbor was at the north tip of the island, and has been reconstructed with pilings outlining where the wharves used to be. I found it a strangely compelling sight: clear contours of a small harbor, yet it’s grass-covered and surrounded on all sides by fields. Next to it is the light beacon and the lightkeeper’s house, but with no sea in sight: just a small pond in the “harbor” and a little stream or ditch through neighboring fields.

Much of the land is now woods, and most of the path is not accessible to cars, so it’s a pleasant walk or bike ride.

Is Schokland worth visiting?

If you have a particular interest in the history of Dutch water control, you’d like this place, especially the museum. I enjoyed it because I like learning about obscure historical events and cultural changes. For many people, though, it’s probably not worth a special trip, unless you are just looking for a peaceful place for a stroll or bike ride.

The museum, however, is very child-friendly. Here and there among the displays are hands-on activities. For example, a small sandbox contains pieces of several broken pots so children can pretend to be archeologists. Another one allows visitors young and old to move “land” to the contours of the area at different time periods. Outside is a big sandbox with a hand pump and movable conduits for water flow, as well as some climbing structures.

If Dutch water control is interesting to you, also visit the D.F. Wouda Steam Pumping Station not far way. Like Schokland, it’s a UNESCO site and illustrates another piece of the Dutch water-engineering puzzle: the largest steam pumping station ever built. In another part of the Netherlands, the famous UNESCO windmills of Kinderdijk are part of the same past and present struggle. The picturesque rows of windmills were built to power pumps to keep the land dry. They are still operational today to supplement the more modern pumping system if needed.

Tips for visiting Schokland

If you’ll only see the museum, your visit will take an hour or less, though with children it’ll take longer. If you plan to walk or bike ride, put aside more time.

The museum charges a small admission fee, but walking or biking around the island is free, as is parking.

If you want to take a bike ride around the island, you can rent one at the museum. There are also some e-bikes for rent in a kiosk outside. Download the Deelfiets Nederland app ahead of time to take one of those, and make sure to return it to the same place since the app charges based on how long you use it.

The museum is mostly wheelchair accessible. The path around the outdoor parts of the museum is also accessible, though it’s a gravel path with a pretty steep incline at one point. You won’t miss much if you don’t go down there. To see the old harbor and lightkeeper’s house, drive to the parking place at the north of the island, and follow the brick path from there. The same goes for the church ruin at the south of the island: you can park near there and then take a paved path.

While you’re in the area, take a drive to the village of Urk nearby. It was also an island in the Zuiderzee until the creation of the Noordoostpolder. Today, though, it is still a fishing village, now on the coast of the Ijsselmeer. A stroll in this pretty town will give an impression of what the Schokland of a few centuries ago might have been like.

Another pretty town nearby is Kampen, to the south of Schokland. With a history as a Hanseatic League city, it has a beautiful and intact old center.

Zoom out on the map below of the region around Schokland and you’ll see a range of hotels nearby. Find accommodations in Urk or Kampen – the prettiest towns in the area, in my opinion – or use the map to see what else is available.

Where is Schokland?

The museum’s address is Middelbuurt 3 in Schokland.

Schokland is in the province of Flevoland, about 15 minutes south of the nearest town of any size, Emmeloord. (Emmeloord, by the way, is also the name of one of the former terp villages on Schokland. This newer town was part of the development of the Noordoostpolder.)

There is no public transportation to the former island. Bus 141 comes closest, with a stop in Ens, about four kilometers away.

My suggestion, if you’d like to get away from the tourist hordes in Amsterdam and other popular destinations, is to rent a car right from Schiphol Airport. Don’t use it to visit cities, which are intentionally difficult to drive in and where parking is expensive. Instead, see what you want to see outside of the cities by car, then return the car to the airport, and take trains to the cities you want to visit.

For more information about Schokland and surroundings, the museum’s opening hours and admission fees, see the museum’s website.

Have you been to Schokland? If so, do you have any additional information or advice about this UNESCO World Heritage site? Please add your comments below!