City of Potosí

By Alex Trembath

What is the City of Potosí?

The City of Potosí is a historic Bolivian mining city situated high up in the Andes mountains, over 4,000m (13,100ft) above sea level. Many of the city’s inhabitants have spent their entire lives at this altitude.

The peak of Cerro Rico – the “rich mountain” – is the city’s defining natural landmark, looming several hundred meters over the rooftops. A network of silver mines running deep inside this mountain made Potosí the world’s largest industrial complex in the 16th century.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. Making a purchase through an affiliate link will mean a small commission for this website. This will not affect your price. Privacy policy.

At the peak of its mining operations, Potosí had a population greater than London or Paris, as its silver extraction fed the Spanish Empire in the Americas. The mines are still active today, but on a much smaller scale, and predominantly for tin and zinc. The silver ore reserves are largely exhausted.

And the city – which is capital of the state (or departamento) that shares the same name – has diminished to being Bolivia’s 8th-largest by population, but the weight of its mining legacy remains deeply imprinted.

Why is the City of Potosí a UNESCO World Heritage site?

It is Potosí’s remarkable mining legacy and its preservation that accounts for the city’s UNESCO recognition. The entire infrastructure of silver production has largely endured to create an industrial open-air museum of sorts, while mining operations still rumble on quietly beneath the mountain.

As UNESCO states it: “Potosí is the one example par excellence of a major silver mine in modern times […] From the mine to the Royal Mint (reconstructed in 1759), the whole production chain is conserved, along with the dams, aqueducts, milling centres and kilns. The social context is equally well represented: the Spanish zone, with its monuments, and the very poor native zone are separated by an artificial river.”

The footprints of the city’s prosperity and social divisions of its mining heyday remain visible through the surviving colonial-era architecture, churches, patrician houses, and the neighbourhoods where the indigenous forced labourers once lived.

UNESCO also notes that the city was economically influential in its heyday, particularly in Europe, because of the “flood of Spanish currency” produced through Spain’s exploitation of the mine, which allowed them to import vast amounts of silver and other metals. At the same time, it influenced architecture in the central Andes “by spreading the forms of a baroque style incorporating Indian influences.”

World Heritage in Danger

UNESCO inscribed the City of Potosí on its List of World Heritage in Danger in 2014 for a number of reasons. There was not a sufficient system in place to ensure maintenance of the historical mining structures and carry out other measures that UNESCO expected, intended to preserve the site and to keep the environment safe for residents and visitors. More importantly, though, UNESCO demands that all mining must stop above 4,400 meters. After so many centuries of mining activity inside the mountain, the mountain peak is threatening to collapse.

While authorities have made various efforts over the years to meet the requirements that UNESCO has set, it remains on the endangered list. Mining continues, and the recommended measures to reinforce and shore up the mountain have not been carried out.

What can you expect on a visit to the City of Potosí?

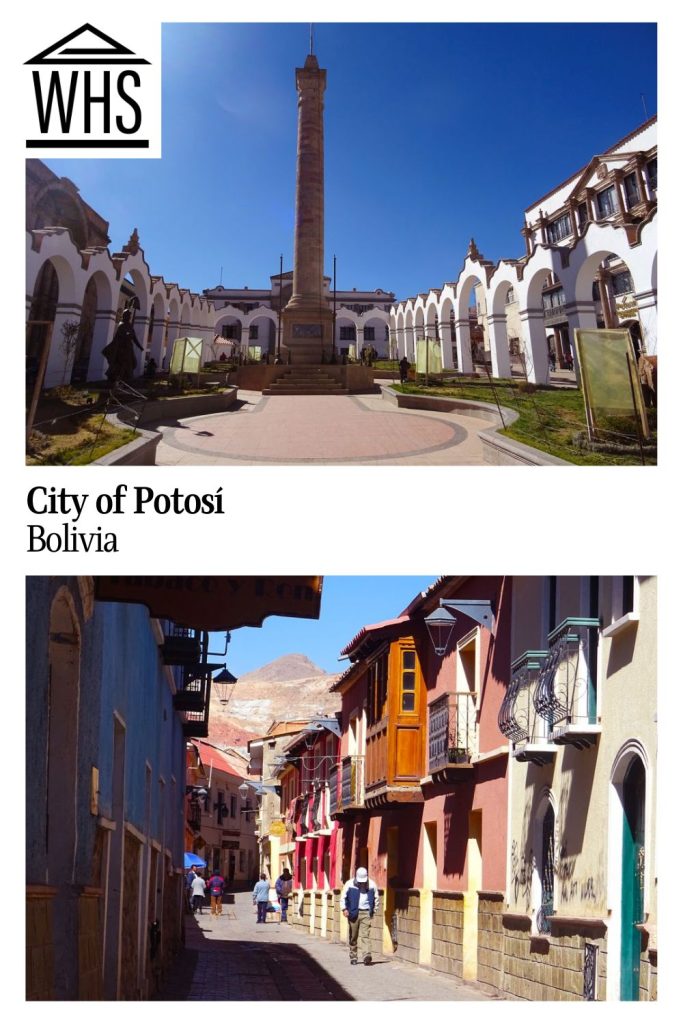

Potosí’s setting beneath Cerro Rico is a dramatic sight to witness as you arrive, and the mountain remains an ever-present backdrop to the cobbled streets, rows of colonial houses and paved plazas as you wander around the streets.

There is plenty to explore around the city’s central zone. Casa de la Moneda – the Royal Mint of Bolivia – last produced coins in 1953, but has been repurposed into a fascinating museum. Occupying an entire block, it gives an insight into the legacy of silver mining and coin production, with well-preserved artifacts and colonial-era machinery on display.

Consider taking a private walking tour of Potosí.

We spent a few days in the city, and simply enjoyed the architecture on foot and uncovering the stories behind it. In Plaza 10 de Noviembre, a compact central square, stands a tall obelisk framed by magnificent white arches, commemorating the rebellion in 1810 that helped bring about Bolivian independence.

But the most authentic way to immerse yourself in the city’s industrial history is to take a tour inside the Cerro Rico mines of Potosí and meet the miners who are still working there today. This is not an experience for the faint-hearted; it is a highly claustrophobic experience beset by numerous hazards.

Cerro Rico’s local nickname is la montaña que come hombres, or “the mountain that eats men.” It is believed to have claimed the lives of thousands or even millions of workers over the years, depending on which account you read. Whatever the reality, there is little doubt that the mines were a lethal place in their heyday. This was due to the extremely harsh working conditions, toxic mercury fumes, malnutrition, exhaustion and the constant threat of tunnel collapses and floods.

The mines are very different today and provide a far safer environment, thanks in large part to the dozens of miners’ cooperatives that have fought for better conditions. It was through one of these cooperatives that we took a tour into the mines. A former miner was our guide.

Our tour into the mountain began with a trip to a local market. There, we were encouraged to buy gifts to give to the miners we would meet later on: dynamite, coca leaves and fizzy drinks. Before entering the tunnels and shafts, our guide kitted us out with protective gear and flashlights, and ran us through the various perils we might encounter. It was at least reassuring to be prepared!

In reality, these tours only scratch the surface of the mines and you are not in any serious danger. There is some clambering through dark and muggy shafts and squeezing through cracks in the rocks, but it is only a tiny fraction of what the workers experience here every day. Many of them toil many layers further underground in suffocating heat. Nevertheless, it is still a relief to emerge back into daylight at the end.

These tours last a good few hours, and you will probably want some nourishment when you arrive back in the city. There is some delicious street food to try around the markets of Potosí, especially salteñas, a baked snack that is like a Bolivian take on empanadas, often made with egg, raisins and olives together with meat and vegetables. In a cosy little local restaurant, we tried a plate of pique macho, a hearty Bolivian dish of spicy fried meats, onions, peppers and fried potatoes, topped with boiled eggs and hot sauce. It’s a bit like a hash, and the ingredients are slightly different wherever you try it.

Is Potosí worth visiting?

If you are travelling in Bolivia, Potosí offers a very different viewpoint of Bolivia’s history and the legacy of empire in comparison to other popular destinations. It’s well worth including in a balanced itinerary to explore the country, or as a standalone visit if you have a special interest in mining heritage.

What sorts of travelers would like Potosí?

Potosí is a strong draw for any travelers with an interest in colonial history, while the active mine tours provide a special appeal for adrenaline-seekers. You can get a flavour of the city’s importance without venturing underground, and the city’s surrounding Andean landscape has great visual appeal, but visiting the mines adds a whole new layer to the experience.

Tips for visiting the City of Potosí

You will need to prepare yourself for the high altitude in Potosí. It stands several hundred metres higher than other popular cities like La Paz, Sucre (also a UNESCO site) or Uyuni. With this in mind, it’s good to build in extra days to acclimatise, take things steadily, and stay well hydrated.

Book accommodations in Potosí using the map below:

At this altitude, the temperature varies greatly between day and night. Pack clothing for all extremes and wear plenty of layers.

Bolivia’s dry season between April and October is generally the best time to visit, although the mine tours run all year round.

While Potosí is gradually modernising, it is still largely a cash economy. Many markets and shops don’t accept card payments, so make sure you have bolivianos handy.

Where is the City of Potosí?

Potosí nestles in the Andes towards the south-west of Bolivia.

By car: Potosí stands on the crossroads of national routes linking La Paz and Tarija, and Sucre and Uyuni, so it is easy to reach by road. It’ll take about 3-4 hours from Sucre or from Uyuni, 10 hours from La Paz and 7+ hours from Tarija.

By bus: We took a bus from La Paz with a stop-off at Sucre. It was a fine journey with some beautiful scenery along the way. The ride from Sucre takes 4 hours, while a sleeper bus from La Paz takes about 10 hours.

Have you been to the City of Potosí? If so, do you have any additional information or advice about this UNESCO World Heritage site? Please add your comments below!